Australia is a giant when it comes to size but a dwarf when it comes to population. Imagine: 26 million inhabitants for a territory of nearly 7.7 million square kilometers. Do the math—or let me do it for you: that’s 3 people per square kilometer. Suffice it to say, there’s plenty of space to breathe, and then some.

For us, this is the third time we’ve explored this country-continent, but this time, we’ve decided to venture even further off the beaten path. No Sydney, Great Barrier Reef, Melbourne, or Great Ocean Road on the itinerary. No, this time, we’ve taken Australia, split it in half, and focused solely on everything to the left. The result? An 11,000-kilometer road trip through endless deserts, wild coastlines, and, at times, a hint of monotony.

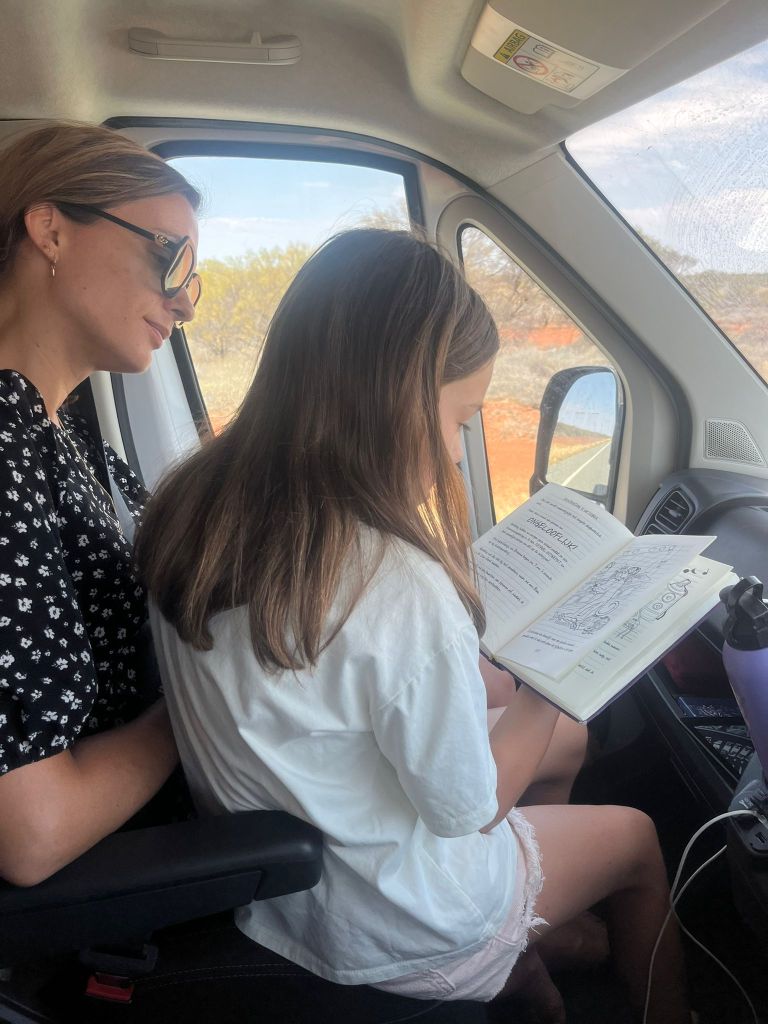

Over the course of these 45 days, we’ve experienced an extraordinary adventure. This roadbook is here to share it all with you: the landscapes that took our breath away, the fascinating—and sometimes dark—stories of this country, and above all, the emotions that have shaped this journey. I dictated 95% of this narrative while driving… maybe that’s why I talk so much about the van… I apologize in advance!

Alright, fasten your seatbelts, let’s go together!

Day -2: before picking up our van

Our plane begins its descent into Darwin. From up here, everything is green, stretching endlessly, with vast expanses that seem to never end. The immensity, already, is impressive.

Darwin, the capital of the Northern Territory, welcomes us. It’s a unique region, an immense and desolate territory. With its 1.4 million square kilometers (2.5 times the size of France) and only 250,000 inhabitants, it’s the least populated territory in the country. So, they have space, a lot of space…

This territory was also one of the last to be colonized by Europeans, who took a long time to get here due to the harsh living conditions. In 1918, there were only 1,500 “white” inhabitants. You can still feel that history today in its culture and population mix. Lonely Planet describes Darwin as a multicultural and vibrant capital. Multicultural, yes, without a doubt: here, Indians, Asians, Westerners, and a significant Aboriginal community, representing about 30% of the population, coexist.

But vibrant? We didn’t really feel that. After several hours exploring the city, we struggle to feel this liveliness. Maybe when you live more than 3,000 kilometers away from the next comparable-sized city, standards differ. Darwin stretches for 25 kilometers, alternating green spaces and clusters of buildings. The downtown area is small and concentrated, consisting of a few bars, pleasant waterfront restaurants, and shopping centers.

We walk back to the city center, crossing the main shopping street. Everything is deserted. Only screams echo in the silence. The kids cling to us, uneasy. A man, Aboriginal, walks by shouting continuously, clearly drunk. The scene is unsettling. It forces us to reflect on the situation of the Aboriginal people, a complex issue I’ll try to address later.

Darwin serves as a practical stop for us: doing laundry (after 10 days, it was about time), stocking up, and enjoying their beautiful waterfront with a natural pool and restaurants.

Day 1: 2 hours of driving, Darwin → Litchfield National Park

It’s the big day: we pick up our van! The kids are bouncing with excitement. Since we told them about our trip, they’ve only talked about the van and their bed suspended above the driver’s cabin.

But before we leave, in Australia, especially in remote regions, there’s a golden rule before hitting the road: fill up. Water, food, fuel… and a bit of alcohol. Why? First, because you can’t always find what you need on the road. Second, because prices can skyrocket once you leave a big city.

3 p.m.: Time to leave. Two hours of driving, and the scenery quickly moves away from civilization. We arrive at a camping site—let’s say… rather minimalistic—at the entrance of Litchfield National Park. Mango trees everywhere, we stock up on fruits.

Australia immediately makes us feel how far we are from our Belgian everyday life. Eating outside here is an adventure: insects pop up from everywhere. A chorus of birds sets the tone at dawn with sounds we’ve never heard anywhere else. This country has a raw magic, born from its isolation for 50 million years when Australia separated from other continents. That isolation allowed its fauna and flora to evolve uniquely, creating species found nowhere else, like kangaroos, koalas, and emus, as well as an impressive variety of reptiles and insects.

And then night falls. Under an ink-black sky, dotted with stars, the Milky Way stretches out in a bright, clear, and fascinating ribbon. We’re far from the neon lights and noise of Japan and China. We fall asleep, already charmed by this wild land.

Day 2: 4 hours of driving, Litchfield → May River

Today, we head toward Litchfield National Park. The day begins with a strange and captivating scene: the termite cathedrals. These structures, several meters high, resemble gravestones reaching for the sky. The setting feels like walking through a giant cemetery. Incredible to think that each of these nests holds 2 to 3 million termites (depending on the species, this is real!).

Next, we enjoy the natural pools, real havens of freshness in the already scorching heat. The crystal-clear water, surrounded by lush vegetation, offers us a welcome break. The day ends with breathtaking panoramas, typical of this wild region.

The journey starts off gently, but we can already feel the adventure waiting further ahead, deep in the Australian bush.

Day 3: 2 hours of driving, Mary River → Jabiru

Today is a special day: the last day of school before a full week of vacation for Nola. After an intense schedule—five to six days a week, one to two and a half hours a day—we’re ahead of the plan. And I believe that, for the first time, Nola is as excited about vacation as we are.

Doing school on the road was non-negotiable. We want her to be at the level of the end of the 4th grade in primary school by the time we return. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Sometimes the lessons turn into battlefields: tensions, arguments, tears… in short, anything but vacation. But we adapt. We adjust our travel pace, we experiment, we learn to be better teachers.

We enter Kakadu National Park, an essential place to immerse ourselves in Aboriginal culture. Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for over 60,000 years. To give you an idea, at that time, Homo sapiens hadn’t yet set foot in Europe. There, it was Neanderthal who ruled, struggling to adapt to a glacial climate. Meanwhile, in Australia, the Aborigines were already developing a sophisticated culture, blending oral stories with rock paintings. Let’s just say that compared to them, Neanderthal… well, wasn’t doing much.

These same Aboriginal peoples lived uninterrupted until the arrival of Europeans only 200 years ago (around 1788, with the establishment of the British penal colony at Botany Bay).

We arrive at Ubirr in the afternoon. It’s 3 p.m., and everything seems frozen in another dimension. The rock faces are adorned with paintings, some over 20,000 years old. But these artworks aren’t meant to be beautiful or admired like paintings in a museum. I wouldn’t say they’re “magnificent,” but they exude something more powerful: they seem alive. They are guides. The Aborigines used them to pass on their beliefs, share their knowledge of nature, and even give survival tips: where to find water, which animals to hunt, or which to avoid.

And then, there’s this painting that fascinates me. A European man, drawn by Aboriginal hands. He’s motionless, almost disdainful. He looks like a spectator who didn’t understand what he’s looking at. It’s fascinating, but also disturbing. This image encapsulates the entire story of the brutal meeting between two worlds: that of the Aborigines and that of the Europeans. A meeting that forever changed the fate of Australia. Here, under the stifling heat of Ubirr, this story still seems suspended.

But this story, I know, I must still share with you… it’s coming.

Day 4: 3.5 hours drive, Jabiru → Katherine

It’s 3:00 PM, and the thermometer reads 41°C. The road stretches ahead of us, straight, endless, crushed under an unforgiving sun. And then, the van starts acting up. No power. Even going downhill, it struggles to go beyond 70 km/h. I press the accelerator, nothing. A climb? We’re at 50, at best.

No choice but to stop. The heat is overwhelming, almost hostile. If we break down here, I can’t even imagine… A car passes every hour. If we run into someone unfriendly, we might be waiting a very, very long time. And honestly, with the heat and our nerves, a fight would be inevitable 😉.

When I open the door, it feels like a weight has fallen on me. The burning air sticks to my skin, and within ten seconds, a swarm of flies attacks us. They’re everywhere.

We stopped near an old mine. Everywhere, signs warn: “Old uranium mine. Pre-1960 standards. Do not touch.” Charming.

We realize we need to change our habits. No more lazy mornings. From now on, it’s wake-up at 6:00 AM, departure before 7:00 AM. Here, the sun calls the shots, and if we don’t comply, we’re going to suffer.

Day 5: 6.5 hours drive, Katherine → Lake Argyle

Today, we have to make progress. We’ve got miles to cover. Too many, if I’m honest. My good resolution from the day before pushes me to get up at dawn. While everyone is still asleep in the van, I head out on the road in silence, alone with the hum of the engine.

First stop: fuel up in Katherine, a town with a significant Indigenous population. It’s 6:30 AM, and the scene is unsettling. Many are here, sitting on the ground or wandering around, like lost shadows. Zombies of another kind. I really need to tell you more about them, about their history, about Australia’s history. But not today. This topic is too important. I want to give it the time it deserves.

And then, there’s the heat. Relentless. Oppressive.

7:00 AM: 27°C

8:00 AM: 30°C

9:00 AM: 32°C

10:00 AM: 34°C

10:30 AM: 35°C

Seriously? Here, you don’t need a watch. The temperature serves as a clock. Every hour, two degrees more.

You can only imagine what European explorers must have gone through 150 years ago, setting out to discover the arid lands of the Australian interior. Guided by the myth of an inland sea, they hoped to find a vast lake at the heart of the continent. But what they discovered was a ruthless desert, where heat and drought reigned supreme.

11:00 AM: 36°C

12:00 PM: 38°C

12:30 PM: 39°C

The kids, at the back of the van, suffer in silence. The heat must be unbearable. Without air conditioning, the interior must easily exceed 40°C. We, at the front, still have a trickle of air thanks to the AC, but even at full blast, it’s hot.

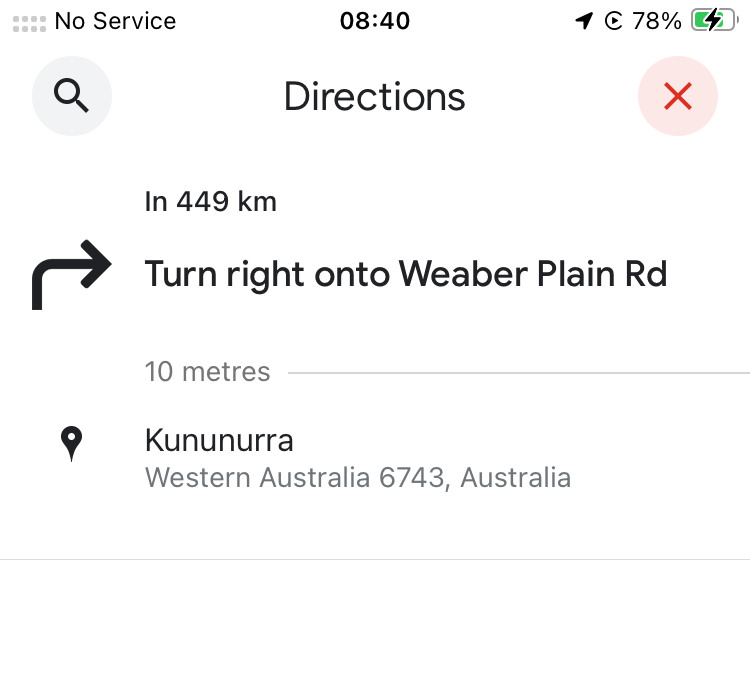

1:00 PM: We leave the Northern Territory and enter Western Australia, the largest province in Australia, covering 2.5 million km². Basically, the state takes up a third of the country.

1:30 PM: 42°C

The road seems to melt under our wheels. Literally. The plastic road signs have sagged under the sun’s assault (no, I’m not kidding), like soft candy abandoned in a too-hot pocket.

2:00 PM: Finally, the campsite. And what an arrival! An infinity pool with a stunning view over the vast Lake Argyle, an impressive expanse of water amidst this furnace. Bliss.

Day 6: 8 hours of driving, Lake Argyle → Fitzroy Crossing

8 hours in the Outback. How do you describe this vast emptiness, this overwhelming monotony, when you’re alone behind the wheel of a camper van for hundreds of kilometers? Let me try.

What is the Outback? It’s everything that’s not urban in Australia, about 70% of the territory. Imagine landscapes that change… rarely. Very rarely. An endless horizon, a few scattered trees, yellow grass scorched by the sun, and this straight, never-ending road. Few bends, few shadows. Just you, the asphalt, and the scorching sun.

Every 200 or 300 kilometers, a roadhouse: a service station, sometimes a caravan park, and with some luck, a small shop. I think the pictures speak for themselves.

Then, every 1000 kilometers, a “village.” Well, village… Don’t picture a charming Italian town lined with cafés and fountains. No. Here, a village means a few dusty streets, prefab houses, and a supermarket that’ll make you miss your local corner shop.

Typical example: Halls Creek, the “largest town” 400 kilometers to one side, and 1000 kilometers to the other. Its 1600 inhabitants have to face isolation in all its glory.

And between these “urban hubs”? Hundreds of kilometers of emptiness. So much so that I find myself noting every cow I spot in the fields or, more morbidly, every kangaroo squashed on the roadside. There are also burst tires left behind, car carcasses worn by time, and sometimes even cows, four legs up, starving to death or crushed by a truck.

This emptiness, paradoxically, gives us time. It allows us to talk about all sorts of things with Suzanne that we would never have discussed before. Childhood memories, the big questions in life, little details that keep us up at night… Those improbable conversations that you can only have when you’re on an infinite road.

Finally, we reach Fitzroy Crossing, a tiny and hot town, where the only available campsite charges an astronomical price for mediocre facilities. But a swimming pool awaits us. And honestly, after a day like that, jumping in feels like a rebirth.

Day 7-10: 5 hours drive, Fitzroy Crossing → Broome

Initially, we planned to spend the night in a tiny town called Derby. But after taking a look around, seeing the famous pier that was advertised as the place to visit, and which, at best, looked like an industrial site (I’ll let you judge from the photo)… we changed our plans.

Two extra hours on the road, and here we are in Broome. After a week of changing places every night, settling here for three days feels like a blessing.

Broome is a little slice of paradise in the middle of nowhere, where the Outback landscapes meet the sea in a brilliant blue.

And the rest?

No worries, the next post is coming soon! You’ll discover how to outrun a 7-meter crocodile (hint: it runs fast, but not for long), why 80 Mile Beach is way bigger than its name suggests, and, most importantly, how the English colonized Australia by massacring the Aboriginal people.

See you soon!

Leave a comment