I left you at day 7 of our road trip in the previous post. Before we dive back into our adventure, as promised, I wanted to take a moment to shed light on a much bigger story: the colonization of Australia. While this chapter began 250 years ago, its effects are still visible at every turn of these vast lands.

How did the Europeans arrive?

As often happened in those days, the story begins with lost sailors. Dutch and French explorers landed here in the 17th and 18th centuries. But it wasn’t until 1770, thanks to James Cook, that British colonization took off. Britain had just lost the United States, and King George III decided that Australia would do nicely as a replacement.

Why? For money, of course, but also because they needed somewhere to send the prisoners overcrowding England’s jails. A brilliant idea: turning a remote island into a penal dumping ground. Here’s an ironic twist: those who committed petty crimes were sent to Australia, while serious offenders faced the gallows… back in England. Swift justice, 18th-century style.

The Aboriginals: hospitality gone unrewarded. Imagine uninvited guests showing up in your garden and declaring it all theirs. That’s exactly what happened. The Aboriginals, who had been living here for… only 60,000 years (a minor detail), initially welcomed the British with peaceful curiosity. Perhaps they thought, “These men in red coats will surely leave soon.”

But they were wrong. In 1788, the British declared Australia to be terra nullius – an empty land, without owners. This meant there was no need to negotiate land rights with the Aboriginals, since, in the eyes of the colonists, they simply didn’t exist. And so began colonization, along with the violence it inevitably brought.

The story of massacres. It started in Sydney, but as colonization spread across the continent, the narrative quickly turned violent. Indigenous populations were decimated by diseases like smallpox and by armed conflict.

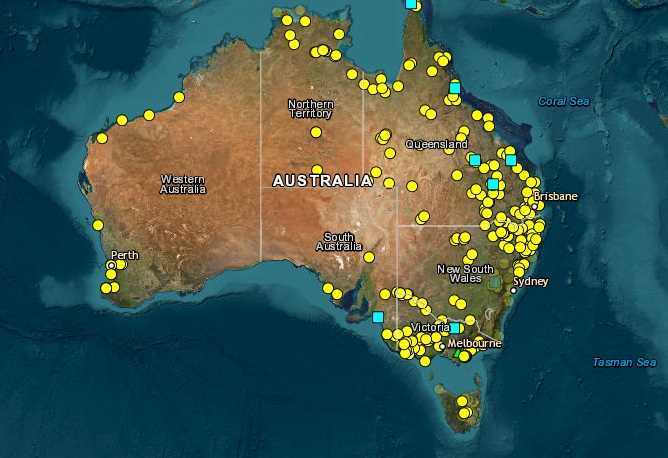

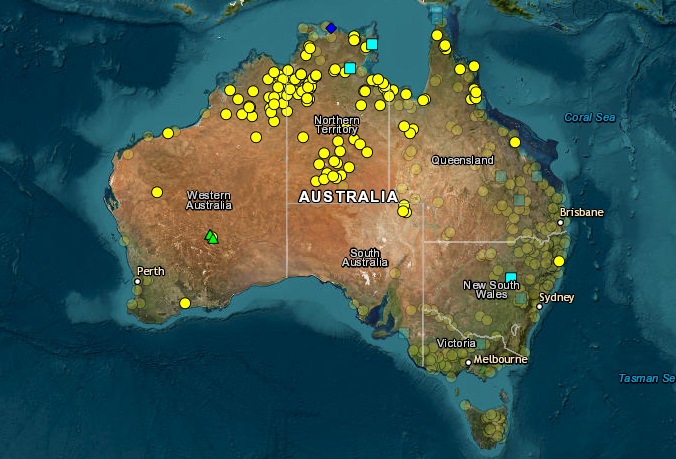

Why? Because the settlers’ expansion came at the expense of Aboriginal land, leading to constant clashes. For over 150 years, massacres were systematic. A map from the University of Newcastle (Colonial Frontier Massacres, Australia, 1780 to 1930, v3) documents these atrocities between 1788 and 1930. It not only shows the scale of the violence but also traces the geographical progression of colonization. Follow the massacres, and you’ll know where the settlers were.

These events, though significant in Australia, are not unique. They are part of a global colonial history, where empires often thrived by exploiting and destroying other peoples, whether they were Native Americans, Africans, or Asians.

Expulsion and Forced Labor. In the 20th century, around 1920, the surviving Aboriginal people were pushed further inland, away from the resource-rich coastlines that attracted the colonists. Ironically, these so-called “useless” lands would be found to be full of gold and coal a few decades later.

As for those who remained near the colonists, they became cheap labor. Exploited on farms, they worked under inhumane conditions until the 1970s. Yes, 1970. While The Beatles were singing “Let it Be,” Aboriginal people were still living a form of slavery.

The Stolen Generations: The Pinnacle of Horror. One of the darkest aspects of this period was the policy of the “Stolen Generations.” Aboriginal children with mixed roots – often from an aboriginal mother and European father – were taken from their families and sent to white foster homes or institutions known as “schools.” The aim? To erase all traces of their culture and train them to become servants for wealthy families or workers for the boys.

And today?

Today, the subject of colonization and the Aboriginals is taught in schools (something unthinkable 20 years ago). Across the country, you’ll find signs acknowledging the “traditional owners” of the land, like in Kakadu National Park, where a plaque reads: “We recognise and acknowledge the Bininj/Mungguy people as the traditional owners of Kakadu National Park.”

Yet the disparities remain staggering. Aboriginals make up about 3.3% of Australia’s population but nearly 30% of its prison population (2019 figures). In rural areas, 90% live in dire conditions, while in cities, they face significant discrimination.

The challenges are immense, and the way Australia was colonized has left a deep and possibly irreversible scar. Aboriginals, long regarded by settlers as “inferior” and “without culture,” continue to fight for their place in a society that struggles to recognize their history and contributions.

In a world where tensions and extremism are growing, it’s crucial to remember that destroying others has never led to anything positive. Education, acceptance, and understanding are, I believe, the keys to building a fairer future.

Day 7-9: 5 hours on the road

Broome is a little slice of paradise in the middle of nowhere. Once the epicenter of the pearling industry—100 years ago, much of the world’s pearls came from here—Broome today is a refreshing oasis after 2,000 kilometers through the bush and a few tiny villages. A favorite seaside destination for Australians, the town welcomes more than 15,000 visitors during peak season. Off-season? It’s calm, peaceful. We set up camp at a spot with a sea view, and honestly, sitting there with a glass of rosé in hand, you can’t help but think, maybe this is happiness.

Life moves slowly here, and we make the most of it, exploring local activities. The local museum is worth a visit, as is an evening at the outdoor cinema—the oldest in the world!—watching Wild Robot under the open sky, a surreal experience.

Another memorable visit is to the crocodile sanctuary. The place is both amusing and fascinating, with a timeless charm. The owner, a true Crocodile Dundee, guides us through the park, feeding these incredible creatures. With his thick Aussie accent, he explains the difference between freshwater and saltwater crocodiles. A little general knowledge lesson: freshwater crocodiles grow to about 1.5 to 2 meters, are relatively shy, and won’t attack unless provoked. Saltwater crocodiles, on the other hand, can grow up to 7 meters and are extremely aggressive. And whatever you do, don’t put them together—saltwater crocodiles would happily devour their freshwater cousins.

Standing just centimeters from them, you quickly grasp one essential fact: this animal is lethal. A killer. Their incredible strength lies in their jaws, capable of crushing anything that comes within reach. Their speed—both in water and when leaping—is astonishing. Imagine hesitating for even a fraction of a second in front of one: it’s already too late. If a crocodile grabs you, it’s game over. You stand no chance.

One final tip from our Crocodile Dundee: if you’re ever chased by a crocodile, forget the zigzag advice. Just run straight, as fast as you can, because crocodiles usually give up after about 30 meters. Who knows, this tip might save your life one day… or at least provide some entertaining conversation at your next dinner party!

Day 10: 4 hours on the road – Broome to 80 Mile Beach

Four hours of driving through a landscape of almost absolute monotony. In Australia, it’s common to drive hundreds of kilometers without any change in scenery. Here, it’s even worse: the road follows the coast, but the asphalt architects decided to build it 10 kilometers inland. So, no iconic road winding along the waves—just distant glimpses of sand.

But the reward comes at the campsite: 10 kilometers of unpaved road later, and you arrive at a beach stretching… 220 kilometers. Yes, you read that right. It’s called 80 Mile Beach (129 kilometers). Why? It’s a mystery.

Maybe the early settlers were drunk when they measured it, or their measuring tools were faulty. Or maybe it’s just a laid-back Aussie rounding: “129 kilometers, 220—who cares? Let’s not nitpick over 100 kilometers.” The mystery remains unsolved!

We spent the afternoon lazily building sandcastles and wading in the tide pools left by the receding sea—the tide here retreats several hundred meters. Oh, and I can already hear your question: Why not swim in the sea? Well, here, swimming is forbidden. Normally, I’m the type to say, “Who cares, let’s do it anyway,” but not this time. In these waters are creatures you don’t want to mess with: sharks, crocodiles, and deadly jellyfish. So, the tide pools suit us just fine.

In the evening, we joined the turtles as they laid their eggs on the beach. In the end, you don’t need much to be happy: a beach, a bit of sand, and a sunset.

Day 11: 6 hours driving – 80 Mile Beach to the entrance of Karijini National Park

Six hours on the road heading towards Karijini National Park, along a route that, in my opinion, would rank very, very high if there were a competition for the most monotonous road in the world.

I’m aware that it’s not the first time I’ve said this…

Today, we encounter road trains—those massive trucks up to 50 meters long that roar across Australia at 130 km/h and need two kilometers to stop. They’re the reason why so many dead animals litter the roadsides. Imagine what happens if you’re unlucky enough to collide with one of these behemoths: 200 tons, 4.5 meters tall, and hurtling at 130 km/h. Need a hint? It’s not a pretty sight.

There are plenty of them today because we’re surrounded by mining sites. As we drive, we move from one mine to the next. Sometimes, you only catch a glimpse of them in the distance, with a few huts or the carved-out hills left behind by extraction activities.

Australia is a true mining empire. The country holds some of the world’s largest reserves of iron ore, gold, coal, and natural gas. The mining sector is a cornerstone of the Australian economy, contributing around 10% of GDP and 60% of exports. The mines, mostly located in the west and center of the country, are often in remote areas, explaining the presence of road trains that haul heavy loads over thousands of kilometers. The landscapes we pass through are clearly marked by this massive extraction, with mining sites stretching endlessly into the horizon.

It’s 1 p.m., 45°C (113°F), and the van is struggling. Maximum speed is 80 km/h downhill, 50 km/h uphill. In other words, we need to stop every 30 minutes to avoid overheating along the way. We’ve got so much road to cover today that we drove until late afternoon, and trust me, it was an experience.

You step out of the van, and immediately a wall of heat at 45°C in the shade slams down on you. And just to add to the fun, a swarm of flies greets you, eager to steal whatever moisture they can from you. You get back into the van, and guess who’s coming along for the ride? The flies. The result? You spend the next 15 minutes trying to swat them dead or shoo them out the window. What a delight.

We’re spending the night at a truck stop roadhouse in the middle of the desert. But hey, good news: the laundry is free. So tonight, there isn’t a single pair of underwear or a single T-shirt left unwashed. What a luxury!

Day 12: 2.5 hours driving – Karijini National Park to Tom Price

We set off at 6:45 a.m. to explore the gorges of Karijini National Park. The thermometer already reads 31°C (88°F)—it’s going to be a hot day. But no matter, we’re here for the gorgeous hikes and, above all, the refreshing swims in the gorges. It’s the perfect opportunity to immerse ourselves in these breathtaking landscapes and enjoy the cool water in the heart of this impressive scenery.

By 11 a.m., the hikes are over… You guessed it: it’s too hot! The rest of the day? Relaxing by the pool.

Day 13: 8 hours on the road, Tom Price → Exmouth

We’re up at the crack of dawn, 6:30 AM, because a long day lies ahead.

First stop: filling up the tank in Tom Price, a mining town lost in the middle of nowhere. It’s got a unique vibe—surrounded by dusty 4x4s, guys in work boots and hi-vis vests chat over their coffees. It’s like the office water cooler, except here, the carpet is replaced by red dust, and the thermostat already reads 32 degrees.

Barely half an hour later, I have to stop. Google Maps has decided to send me onto a gravel road. Sure, it’s the shortest route, but 250 km (155 miles) of bumpy track in a 4-ton, 2WD van? No, thank you. Ten or twenty kilometers might be doable, but this is the kind of decision that ends with headlines in the Belgian papers: “Four Belgian tourists vanish in the bush; $10,000 fine to retrieve their van.”

I pull over randomly and flag down a Toyota Hilux driven by a miner who kindly stops to help. With her thick Australian accent, she explains how to take a detour. The verdict? Two extra hours of driving. Great. I feel a bit silly—after covering more than 20,000 km in Australia over the years, I’m still falling into rookie traps like this. But that’s how it is. Besides, it’s back-to-school day, so more time to get back on track.

The scenery? Still bone dry, flat, and depressingly monotonous. Not a drop of water under the bridges. A few hills occasionally break the horizon, but it’s still desert as far as the eye can see.

Oh, and a quirky little gem along the way: we spot a mailbox planted on the side of the road. I look around—no house in sight. Google says the owner lives 88 km (55 miles) away. I guess they don’t check their mail every day.

Finally, after what feels like an eternity (with a few stops so everyone can stretch their legs), we arrive in Exmouth. Thirteen days, 4,500 km (2,800 miles) covered, and nearly 60 hours of driving.

Tonight, it’s full-on relaxation. We’ve definitely earned a few days here to recharge our batteries… and those of the van, of course.

And you’ve earned a break too! The next post will be coming soon, assuming my laptop doesn’t give out again like it has for the past ten days.

Take care and lots of love from us to you!

Leave a comment