7. Brasília, May 14–18, 2025

10 a.m.

We thought our rental home had a washing machine… nope. We have ten days’ worth of clothes, not one day more. So here I am, at the neighborhood’s laundromat. The place is super modern, almost clinical. But as is often the case in Brazil: no CPF, no service.

This infamous CPF (like a personal, national number) is your golden ticket. Without it: no washing machine, no SIM card, no Pix (Brazil’s favorite instant payment system), not even a discount at Zara or the bakery. Seriously, what does the government have to do with my dirty laundry?

For foreigners, Brazil can feel like a snake eating its own tail: you need a CPF to open a bank account, but you need to be a legal resident to get a CPF… and to be a legal resident, well, you often need to already be in the system. Luckily, there’s always a plan B: a WhatsApp number, a credit card workaround, or a well-placed contact.

And often, it’s the disarming kindness of Brazilians that saves the day. At the laundromat, a gentleman even offered to use his own CPF for me.

End result: I walked out with clean clothes and a genuine smile.

But this CPF thing also symbolizes a certain Brazilian inwardness — almost charming, in a way. There’s a very… local relationship to the world here. As if Brazil were the center of the Earth, and everything else some optional folkloric footnote. Geographic knowledge is often basic, foreign culture boiled down to clichés, and there’s this unshakable belief that Portuguese is a global language. “Wait, your kids don’t speak Portuguese?” someone asked us, genuinely baffled, as if it were the equivalent of English.

And this isn’t just the impression of a laundry-weary traveler — it’s been studied by sociologists, educators, and political scientists. Several studies show how the combination of a very inward-looking education system, firmly domestic media (after football, carnaval, and telenovelas, there’s maybe a bit of world news), and a… let’s say modest approach to language learning all help cultivate a slightly tropicentric worldview.

The result? Brazil looks at Brazil, speaks Portuguese with itself (my six months of Duolingo actually helped a lot!), and tends to see the rest of the world as a slightly dull version of Bahia. Brazil isn’t outward-looking. It is its own world. And honestly, when you look around, can you really blame it?

But let’s get back to the point: Brasília.

We hadn’t planned to stop here — but how could we not visit the only 20th-century city in the world to be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site? This place is a magnificent anomaly. A capital city built from scratch in the late 1950s, right in the middle of the country. Brasília is a dream turned concrete — an architectural manifesto, a modernist utopia brought to life in just 41 months.

In the 1950s, President Juscelino Kubitschek launched a titanic project — one that would be unimaginable today: move the capital from Rio de Janeiro to the country’s interior. To an isolated, remote location, in the middle of nowhere. Over 1,500 kilometers from the beaches of Copacabana.

The goal: develop Brazil’s interior and break the dominance of the Rio–São Paulo axis. But more than geography, it was about building a dream — a modern, daring, futuristic Brazil.

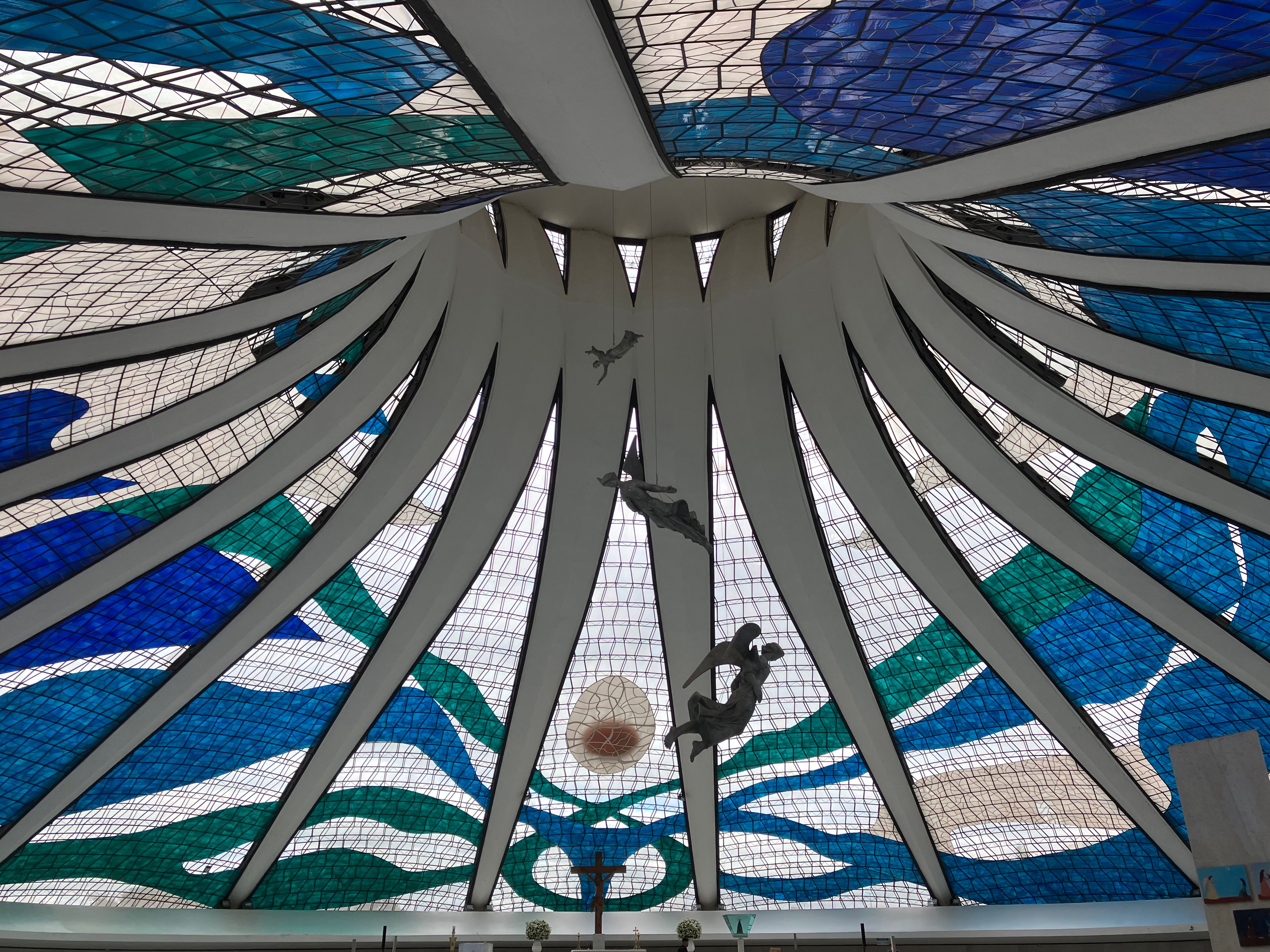

The result? A city shaped like an airplane — literally — filled with futuristic buildings designed by Oscar Niemeyer, the great architect of Brazilian modernism. His cathedral with its heavenly curves, the twin-domed Congress, the residential blocks conceived as self-contained living modules… everything here breathes the 1960s and its blind faith in progress.

Brasília today: between dream and reality

Brasília was born from a dream: that of a modern country, looking to the future, egalitarian, rational, and carefully planned. A city designed for its citizens, far from the chaos of old colonial metropolises.

But sixty years later, the dream is cracking. As soon as you leave the center, the promises evaporate: massive traffic jams, neglected suburbs, spatial and social segregation… Brasília is now a metropolis like many others, with its contrasts, challenges, and disillusionments.

A dream set in concrete.

And perhaps that’s the cruelest symbol of all: in 2025, Brazil looks much more like its disorganized outskirts than the urban ideal envisioned in 1960. Kubitschek’s grand project — a united, modern, ambitious country — has crashed against a now-familiar reality: corruption, inequality, violence, and a failing education system.

1. A political system plagued by backroom deals

During our visit to the Senate, we’re shown glossy videos celebrating Brazilian democracy. Behind the scenes, it’s a different story: cronyism everywhere, quid pro quo arrangements, votes traded for favors… Deputies vote according to what they get in return, and meaningful debates are rare.

2. A rentier economy, fragile and undiversified

Brazil is vast, fertile, and rich in natural resources — and that’s part of the problem. It’s a rentier country that relies on commodities (soy, beef, minerals) without ever truly industrializing. The result: deindustrialization before actual industrialization. When global commodity prices fall, the economy crashes. Weak governance means the state takes the path of least resistance, behaving as if its resources were infinite — and the environment pays the price, sacrificed for more crops and cattle (over 200 million head).

3. An education system in crisis

It’s hard to imagine a different future when schools struggle to teach the basics. Inequality in access to education, poorly trained teachers, and outdated curricula are holding back a generation that could rethink and build a new future.

4. One of the world’s most unequal countries

No need for lengthy studies — just open your eyes. Here, wealth has a color: white. Afro-Brazilians and Indigenous peoples still overwhelmingly occupy the lowest rungs of the social ladder. The wealth gap is five times wider than in Europe. And this structural violence feeds very real violence: cartels, police brutality, neighbor disputes. A French expat confided he avoids drinking too much at parties: “People here have an itchy trigger finger.” The homicide rate is 30 times higher than in Europe. This constant atmosphere of tension paralyzes the country.

To be honest, I’m not very optimistic about Brazil’s deeper trajectory. The informal economy (undeclared work) deprives the state of revenue, and therefore of redistribution. The society is polarized, violent, and disillusioned. Some are already fearing — or hoping for — Bolsonaro’s return. Or worse: the rise of one of his sons.

Fixing all this would require a string of bold reforms, led by competent leaders. And in Brazil, those seem about as rare as jaguars in the Pantanal.

But the future is never written in advance.

So, rather than trying to reform a country, we decided to do what we do best: raise a glass at a vineyard. Yes, after two and a half months in Brazil, we still hadn’t visited one. Scandalous. But the mistake has now been corrected.

We headed to Vinícola Brasília, about an hour from the capital, one of the few wineries on the Central Plateau. And there — a real surprise. A very pleasant visit, genuinely excellent wines, with special mention to the rosé and the red. A proper tasting, done right.

The detail that blew me away? Here, the grape harvest takes place in winter. Yes, right in the middle of the southern winter. Because in summer, it’s simply too hot and it barely rains. So the winemakers came up with a clever solution: a double pruning technique, in September and March, to trick the vines into thinking winter is actually the best time to bear fruit. Clever, right? Brazil has even become a global pioneer in tropical viticulture.

Just goes to show: when it comes to making good wine, humans are capable of anything. Absolutely anything.

8. Northeast, May 18–24, 2025

We leave the soft sunshine and blue skies of Brasília and land in the steamy clouds of northern Brazil, in São Luís. Clouds, heat, humidity — the trio that will follow us for these final five days.

Last stop on this two-and-a-half-month odyssey through Brazil… and we’ve saved the best for last: the dunes of the Lençóis Maranhenses, a place many consider the most extraordinary in the country.

We land in São Luís, then hit the road for four hours to reach the village of Barreirinhas, the gateway to the park. On the way, nothing much to report — but you can feel it: we’re back in the North.

The roads are bumpy, and the repair attempts look like big band-aids stuck on a wooden leg. Poverty is more striking here. Few houses are solidly built. At best, buildings with exposed red bricks, as if the plasterers were on strike

And don’t bother looking for a refined restaurant — there simply aren’t any.

The next morning, we set off in a massive Toyota Hilux: the track is a minefield of craters. When we reach the foot of a dune, we continue on foot. Once at the top — shock. A hallucination? A tropical mirage? And yet, nothing here is a mirage.

Close your eyes for a moment. Picture a vast field of dunes, like a desert, with white sand so pure it feels almost unreal.

Now imagine each dip between the dunes filled with water. Turquoise, crystal-clear water, where the sun reflects like glass.

And if you really want to go all in, imagine yourself swimming in these lagoons: the water is soft, slightly cool…

Got it?

Well, we were there.

The sand comes from far away. From the Amazon, in fact. It’s carried by ocean currents to the coast of Maranhão, then pushed inland by the trade winds. The result? A sea of shifting dunes that slowly advances, as if trying to swallow the forest.

But it’s the water that brings the magic. From January to June, the rains are heavy, tropical. They fill the hollows between the dunes, forming hundreds of lagoons. And here comes the surprise: the water stays. Not just for a day or two — sometimes for months.

Why? Because beneath the sand lies a compact, impermeable layer of clay. A natural, invisible lid.

The result? The water doesn’t seep away. It lingers. It waits. It captures the light.

And for a few months, the desert becomes an oasis.

Then everything evaporates with the return of the dry season — as if none of it ever existed.

An almost unreal cycle. A well-kept secret.

While the Iguaçu Falls are known around the world, this timeless place remains largely undiscovered.

And in the middle of this timeless setting, we happen — by pure chance — to meet other travelers.

2 evenings shared together, laughter, stories, and the all-too-familiar struggles of parenthood.

Talking about the joys… but also the meltdowns, and those moments when the kids are just a bit too much.

It felt good. A lovely, simple, and genuine encounter.

We close this gigantic Brazilian chapter with two days in Belém, the gateway to the Amazon.

And what a chapter it’s been.

Two and a half months, eight regions crossed, breathtaking landscapes, fascinating cities, sometimes brutal contrasts — but above all, a full immersion into the wild diversity of this continent-country.

No regrets about staying this long.

We didn’t just skim the surface of Brazil. We lived it.

We tasted its kindness, hiked through its chapadas, explored its natural wonders, played football on its beaches — and above all… we got lost in its contradictions.

And along the way, we adopted the caipirinha.

Before we set foot here, Brazil was a big question mark on our itinerary. A vast unknown.

Today, like always when traveling, the country has been demystified. Complex, contrasting, far — very far — from the clichés.

But for us, it will remain a powerful, rich, and deeply moving part of our journey.

We hope that our five-part Brazilian odyssey has made you want to come spend a few weeks here too.

Big hugs from us!

Leave a comment